In 2021, I almost burned out. It lead me to question a lot of things about myself, the work I do, and how it affects me.

This post is not about how I got there (you can read about that here if you’re interested), it’s about one of the core challenges I think we face as IT professionals and the lessons I learned moving forward.

The thing about software is…

… it’s never really done. Anyone who has written software that is used daily in production knows this. By done, I don’t mean that the features are frozen or all known bugs are fixed. Software needs attention, and it can break through no fault of your own.

Some random examples include:

- An SSL certificate of an external dependency expires, and your software stops working. From the outside, this looks like your software stopped working, not theirs.

- An Android app is not compatible with the latest version of the OS and needs to be updated lest it be removed from the Play Store.

- A credit card used for paying for a cloud service expires or is no longer accepted.

So, what do businesses that rely on software but do not have or want the personnel to maintain it do? They outsource care, through support contracts.

Support contracts

Support contracts can be a good deal for both sides. Clients receive a commitment that you will take care of their software for them. In return, you profit from recurring revenue after the initial development phase concludes. If you did your job well, your software will require little maintenance, and you get paid mainly for “being there when you’re needed.”

By committing to supporting software, you take on responsibility. If the responsibility rests on many shoulders, like in larger companies, everything’s fine. But if you are a tiny company or even solo, once you start taking on too much responsibility, it can become problematic. You just have too much leverage.

Leverage

In the physical world, it’s unthinkable that a single person can run the operations of an entire building — from keeping its foundations intact, plumbing, electricity, and heating to guarding the building entrance, it’s clear that this is a job for a team of people.

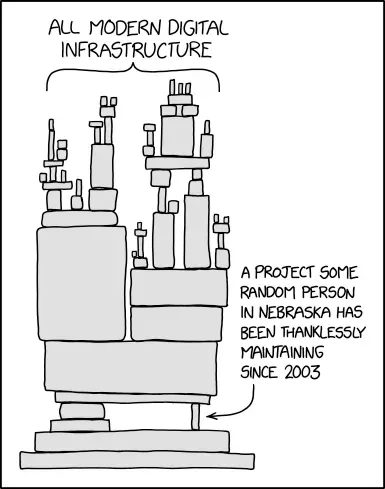

But in the virtual world of software? Not a problem. A single individual can create entire landscapes on their own by using their leverage. The canonical illustration for the kind of outsized influence an individual can have is, of course, brought to you by xkcd:

The leverage a Software Engineer has, compared to say a bricklayer, in my opinion comes from mainly two things:

Experience — the 10x engineer may be a myth, but having done something a couple of times already can speed things up by factors that you wouldn’t think are possible. In contrast, a bricklayer can not build a wall ten times faster because he’s built similar walls in the past.

Existing code — when you’ve been around the block, chances are you can pull something out of your stash, adapt it, and make large strides toward completing a project fairly quickly. A bricklayer can not reuse an existing wall to build a new house.

You could argue that existing code is materialized experience, so in the end, it’s mostly experience.

What does that mean? It means the better you do your job, the more responsibility you will accumulate. Thanks to your leverage, you build out all this stuff, and in the rest of your time, you can build more stuff, which eventually turns into low-maintenance projects, etcetera, etcetera.

Walls eventually cave in, but the software doesn’t just disintegrate over time. In theory, it could run indefinitely.

The weight of responsibility

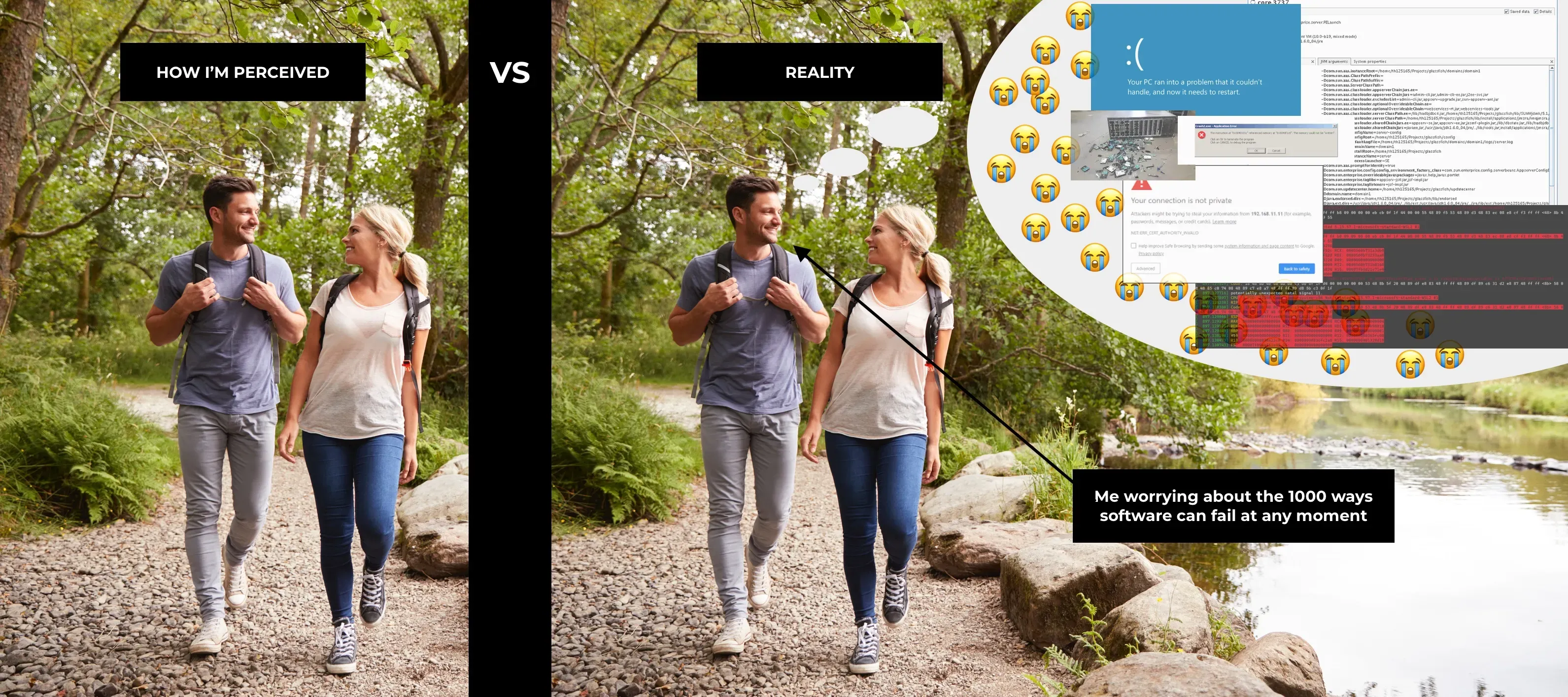

What started happening to me back then was I accumulated ever more software that was basically working fine, but you’d never know when something would break. And things break all the time. In a sense, I felt like I was always on call.

Eventually, it started to weigh on me. I had trouble sleeping, my mind was busy going through “what if” scenarios, and at times I felt paralyzed — like being afraid to go outside because you never know when you could get struck by lightning.

This can be hard for people to understand. You’re not doing anything right now. Why aren’t you relaxed?

Eventually I realized that the majority of stress factors in my life were in one way or the other related to this burden of responsibility. Once I figured that out, I was able to adapt accordingly.

Lessons learned

What follows is a non-exhaustive list of personal principles and guidelines that I follow to keep my mental health intact.

Choose your battles wisely

Especially early on, when you are starting out, say as a freelancer or as a young agency, it’s tempting to say YES to everything. You need new business, build a reputation, and all that.

It doesn’t get much easier later on, especially if you suddenly have larger costs to cover (salaries) and maybe more personal expenses as well (kids, a mortgage, etcetera). Financial pressure is just one of the factors — not wanting to disappoint clients, especially existing ones, is another.

Saying NO is hard, but it’s the ultimate skill to have. I worked hard to be in a position to say no. A potential project needs to be aligned with my strategic goals and has to tick the right boxes.

Build with support and maintenance in mind

When I build software for a client, I don’t just think about its functionality, I also try to envision how my client will live with it. Ask yourself: How hard would it be for the client to give this to someone else? How much effort would it take to train someone to operate and maintain it?

Modern cars can serve as an analogy here — they’ve become so complicated that only trained technicians can service them, and typically these technicians are trained on a specific make. Older cars were much simpler, and were regularly serviced by their owners.

Try to build with simplicity in mind, using standard and widespread technologies, avoid unnecessary dependencies and make support and maintainability a priority. Start writing an Operations Manual early on (while you’re developing), and add to it every time you do something that a client may need to do again in the future.

Own your risk

Use dependencies with care. Third-party libraries generally speed up development but tend to introduce problems later in the software lifecycle. Dependencies can get stale and eventually abandoned, and they can introduce risks, especially in security-critical software. Dependencies can make your software harder to update. Some dependencies are so ubiquitous that they can’t be avoided and treated as part of the platform (e.g., NumPy for Python). Pin dependency versions.

Invest in making your build process robust and as accessible and transparent as possible. Your build executors should be versioned container images (e.g., GitHub container actions). Let the build run periodically even if there are no changes in the codebase to detect problems early, not when the customer needs a new release. One of my worst nightmares is trying to reproduce a snowflake build environment for some “it builds on my machine”-project on a deadline.

Own your distribution channel. For instance, distributing through the App Store can’t be avoided for iOS native apps —but do you really need a native app? Maintaining an App Store presence is a great way of ensuring you have to do boring work with no benefit to the client on a regular basis. I’ve had apps removed for policy violations because the “ACTION REQUIRED” emails went to a mailbox the client doesn’t read.

Be honest

When you’re trying to land a project with a large client, your company’s size is often asked when the client does due diligence. Some firms won’t do business with small shops, so the temptation arises to make yourself appear bigger than you actually are. Impressive web pages with an inflated Team section (with most people actually not working for you) are an example that comes to mind.

Don’t do it. Be honest about who you are and what you can offer a client.

Of course, I’m still figuring things out and always learning, so I appreciate any comments and suggestions you might add.

Thanks for reading!